The Spiraling Shape will make you go insane

Everyone wants to see that groovy thing–They Might Be Giants

The chambered nautilus is sometimes called a living fossil. It is the closest living relative of the ammonoids, and cross sections of its shell are familiar to every adult in the western world. Most kinds of ammonoids lived a long time ago. They started appearing in our Devonian strata around 415 million years ago. Pretty cool, since modern humans have been around 0.195 million years. If you consider the chambered nautilus close enough, then you might say that these critters have been around 2000 times longer than humans. That is real staying power.

In June my wife and I visited San Francisco for a vacation. A delightful city for touring because it has such a mix of old turn of the 20th century buildings, awesome bridges, a cool sea breeze, great parks and museums, shopping, cultural diversity, and enough hipsters to feed Cthulhu for an eon. Unless someone can find a more suitable use for hipsters.

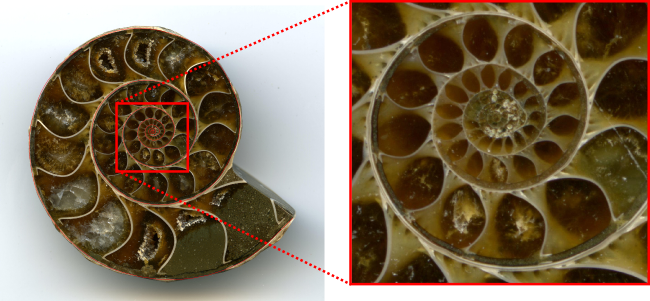

In Chinatown we saw all the usual junk. But there was also a rock shop that had a nice assortment of cross-sectioned fossil ammonoids or nautiloids. I dug through and looked for one with the most open inner spirals. And here it is.

I scanned it at absurdly high resolution, the largest diameter is 1.6 inches. The construction of the nautiloid is fascinating. The spiral is logarithmic, as you can find asserted all over the web. Of course, in my entire life I have never seen anyone actually measure the spiral and show its logarthmic nature. But it looks like it a logarithmic spiral.

The structure is self-similar. It is hard to tell how big this little shell is because it would like basically the same to your eye at ten times the size. I love that: fractal without fragmentation. The creature, I suppose, could grow large just by repeating the same basic step—grow a new chamber. The genetic code to scale up must have been quite an innovation, evolutionarily speaking.

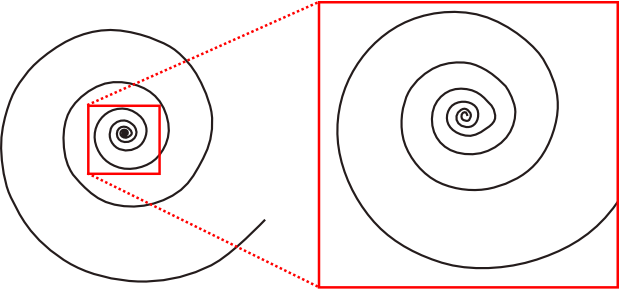

Distilling the spiral of the shell to its simplest shape shows awesome, but not perfect, consistency.

I have never seen a discussion of how the maximum and minimum buoyancy of the creature might have changed as it grew. You can bet that there is a clever relationship between the mass of the cephalopod’s body, the mass of its shell, and the volume of each successive chamber, at least for those that can move vertically. Seafloor-dwelling species might be marked by a faster-opening spiral that keeps their shell from rising. Why is that a safe bet?

I understand that the nautilus spends the day deep in the ocean, and rises near the surface to hunt at night. They control their depth by pumping water in and out of their shell chambers. A nautilus’ chambers are connected by a little hole, and I can’t see any holes between chambers in my fossil so maybe mine wandered about on the seafloor or floated at a constant depth.

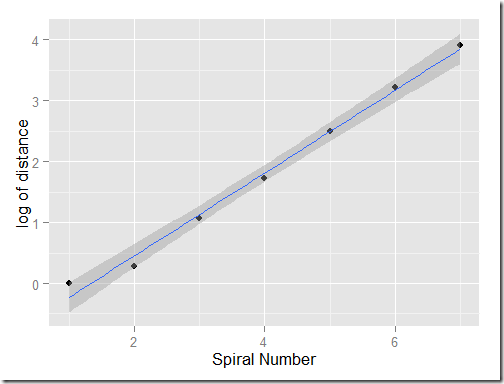

I measured my trace for the distance between spirals. I divided them all by the smallest one and produced the measurements

| 1 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 5.6 | 12 | 25 | 49 |